These days, tariffs and trade wars come up in almost every conversation. Unlike other topics, it is not exactly trade, but the relatively opinionated comments about it that the topic is becoming an increasingly polarising issue.

The sweeping comments I’ve heard range from statements such as:

‘Free trade is good for society and everyone is better off.’

‘Tariffs will work to bring back jobs and lead to a revival of manufacturing.’

And even a CEO recently said that ‘it’s unambiguously horrible, horrible economic policy.’

Very often, politicised issues tend to produce the most polarising discussions. The topic of trade is now a political issue. It doesn’t help that trade is an economic issue that affects businesses, jobs and society. And like every economic issue, it’s usually quite difficult to be certain about the outcome of an exact policy.

We can only generalise and study the past to broaden our perspectives.

What We Know From The Past

Economics is often called an incomplete science because it’s difficult to be scientific about it. The markets and economies are incredibly complex with many multifaceted phenomena. Gathering relevant data forming a hypothesis and then testing a hypothesis is almost impossible. And if we can’t do that, then all statements become mere postulations that are open to debate.

So for every economic thesis out there, you can almost find an argument for it and a counterargument against it.

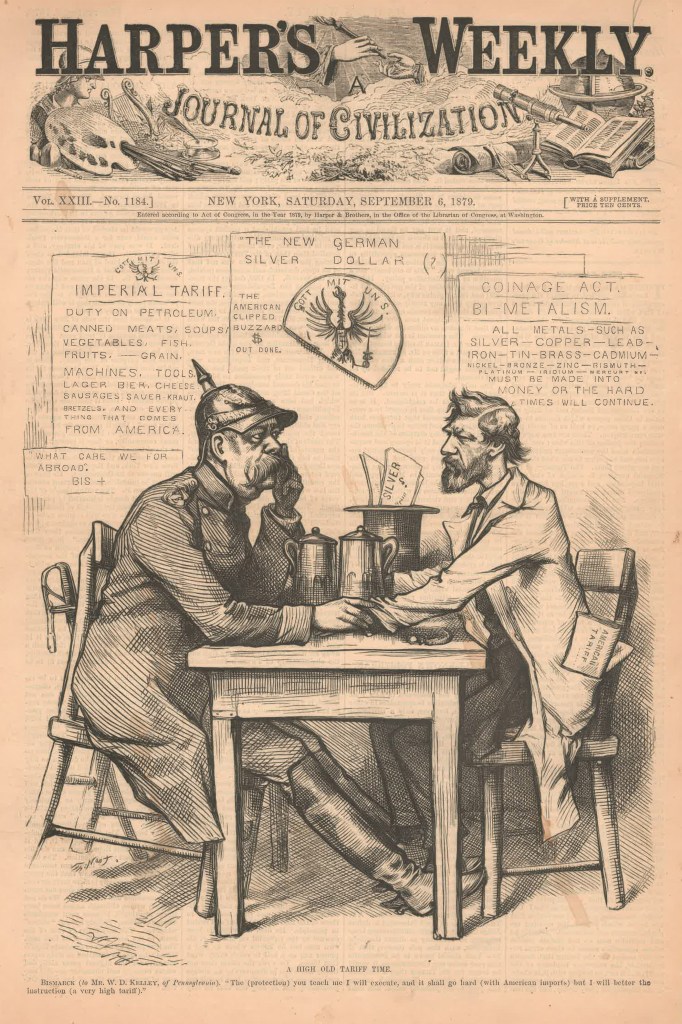

On tariffs, many seem to link it with protectionism and conclude that they don’t work. However, during the Bismarck era, Imperial Germany actively employed tariffs to great success. Tariffs were used to protect agriculture and industry while competing against British industrial might (read about the ‘Roggen-Eisen Koalition’). The Kaiser’s government also invested heavily in science and engineering, which led to productivity gains and rapid industrial growth by the end of the Victorian era.

Another example from as recent as the 1950s are South Korea and Taiwan. Both countries employed tariffs as parts of their import-substitution policies to promote exports and protect key sectors such as chemicals, electronics and steel. These policies were implemented alongside strong state planning, education and infrastructure development.

In both cases of Imperial Germany and South Korea and Taiwan, their respective tariff policies were part of a deliberate, targeted economic plan and achieved the intended outcomes.

On the other hand, many are familiar with all the instances where tariffs didn’t work (for example, the trade wars of the 1930s that followed the Smoot-Hawley Act). There’s a lot of literature out there explaining the harms of tariffs and touting the benefits of free trade. And of course, many of us have benefited from trade globalisation in the twenty-first century.

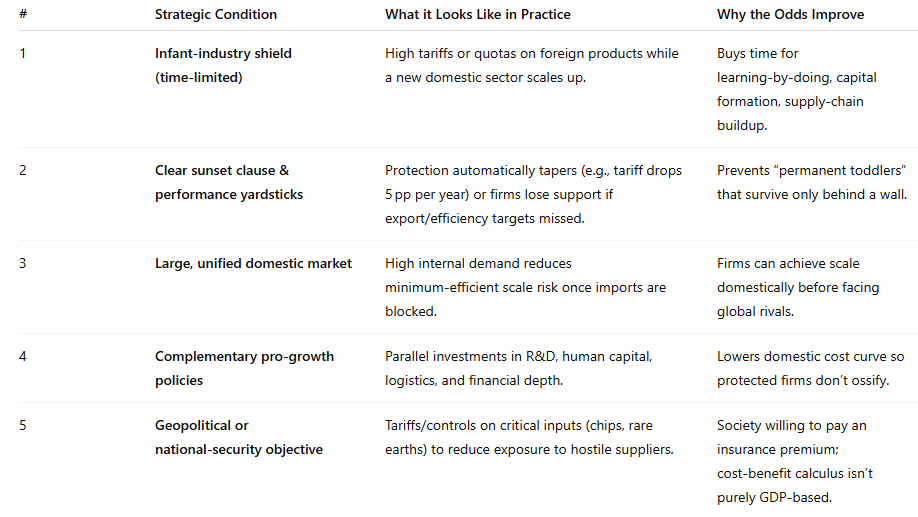

But by observing the past, we’ve learned that the difference between success and failure of tariff policies are a set of narrowly-defined conditions and a deliberate and targeted coordination of various economic policies. GPT gave me the following strategic conditions when trade barriers tend to ‘work’:

Secondly, the angst against free trade isn’t new. Trade globalisation has occurred multiple times in the past. The economic historian William Bernstein wrote in A Splendid Exchange:

Change always makes some people unhappy. In the new global economy of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, textile manufacturers, farmers, and service workers were all hurt by cheaper and better products from abroad. They were just as vociferous then as French farmers and American autoworkers are today.

They were always losers in trade globalisation. Bernstein noted that these disruptions created political backlash throughout history. Societies have always struggled to balance the overall benefits from trade against its concentrated harms. These dynamics were seen across various cultures and tensions, and the rhetoric was very similar across different periods of time.

Thirdly, trade globalisation tends to occur when there is a hegemon. An economic and political hegemon allows integration of trade routes, exchanges between different societies, and the movements of people. Other than goods and technology, ideas and religions could spread. The brutal conquest of the Mongols in the 13th century expanded their empire from the Tonkin Gulf to the Crimea, opening up the vast Eurasian steppe to merchants from East Asia to the Middle East and the West.

The Iberians’ exploration allowed pepper and spices to reach almost every viable port in the sixteenth century, while in the 19th century, the British Empire enforced trade through sheer naval might during its heyday. A hegemon also subsidises the costs of trade globalisation. Whether it’s the dusty, arid steppes of the ancient Silk Road or the crucial sea lanes of the Aden Gulf, militaries typically are deployed to police against bandits and to enforce taxation. Safety for commerce allows quicker and cheaper (just think of insurance) voyages for goods to move.

This also means that when there’s an absence of a hegemon, or when there are too many fragmented political entities with differing interests, trade globalisation is a lot harder. In fact, the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century could have led to the drastic collapse of trade volume across Europe and the Mediterranean in this context.

The Real Issue Is Wealth & Income Redistribution

U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent highlighted in an interview that in the summer of 2024, he read that a record number of Americans are having holidays in Europe, while a record number of Americans are showing up at food banks. And this is why he was onboard with President Trump’s tariff plans to revive the middle class in the U.S.

This is the key issue of our time – the gulf between the haves and have-nots. Whether it’s using Gini coefficients or income disparity readings to measure, the wealth divide today is at record levels across most countries. History has also shown that this dynamic has occurred in previous times of global prosperity and trade globalisation (like the late-Victorian era) – the gains from booms and free trade just don’t accrue evenly. And when the divide gets too extreme, divisive societal changes usually occur.

Financiers, businessmen/industrialists and knowledge workers have benefited a great deal from trade. On the other hand, those that have benefited less or even adversely impacted are those affected by trends of outsourced manufacturing and services. In some sense, Wall Street’s interests are aligned with big state-supported exporters in export-reliant countries. So trade wars are essentially class wars, aside from geopolitical tensions or nation-to-nation rivalry, and as long as the divide is there, the angst against free trade is here to stay.

Policymakers all over will have to address this key issue of wealth redistribution in our time.

It’s clear that the Trump Administration is using tariffs as a policy tool to address the issue of the wealth divide by trying to create investment, jobs and revive the middle class. Until there is a well-orchestrated economic plan, we can’t be certain that they’ll succeed. Also, it’ll take years and a coordinated national effort, so the next administration has to continue implementing without getting distracted. We wouldn’t know if tariffs will be used as a policy tool as well.

The Trump Administration’s focus on domestic issues is also a sign where the U.S. (current hegemon) is unwilling to subsidise trade globalisation anymore. It doesn’t necessarily mean that global trade will collapse, but what is obvious is the gradual reordering of trade systems and trading relations. And this will continue for years and even decades to come.

Where Do We Go From Here

Now that we know what the real issue is (wealth and income redistribution), we’ll also be hearing a lot of discussions over taxation, debt restructurings, state-capitalism or dirigisme, and mercantilist measures in many liberal democracies. Additionally, given that the angst against trade globalisation is here to stay in some countries, ambitious populist politicians are likely to fan fires and ride this sentiment to power (never mind if their perceived policies succeed or fail).

As for the U.S. Dollar’s role as a reserve currency, it’s unlikely to ‘collapse’ as some pundits claim due to the lack of a viable alternative, but there’ll be more diversification away from the greenback (further thoughts here). There’s a role for Gold and Bitcoin to some extent, despite their lack of any real-world use.

And as for trade and tariffs, it’s an age old issue that remains controversial and challenging for any of us to be certain of its benefits and harms. What we do know is that trade will continue to shape our societies and lives just as much as it did in the past.

Leave a comment