Source: https://www.artchive.com/artwork/the-swallow-s-tail-salvador-dali-1983/

Salvador Dalí’s last painting is ‘The Swallow’s Tail‘, which he finished in May 1983.

At first glance, it may be hard to understand its essence.

The artwork stands out with its geometric, fluid forms and with the contrasting red curves and black lines. Elements of the piece stretch beyond the implied boundaries, leaving you with some sense of expansion beyond the physical frame.

When he painted it, Dalí had in mind René Thom’s mathematical catastrophe theory.

The shape of Dalí’s Swallow Tail is from Thom’s four-dimensional graph of the same name. He combined it with a second catastrophe graph, the S-curve dubbed ‘the cusp’. Dalí presented Thom’s model alongside the smooth curves of a cello and the instrument’s f-holes, which looks like the integration symbol from calculus.

Thom’s theories attempt to model dynamical systems: classifying phenomena that could see sudden changes in behaviour when small changes in circumstances take place. Like that of a landslide. Catastrophe theory is the study of dramatic transformations from order to disorder.

This sounds like financial markets. If you look at market history, you’ll tend to see that markets alternate between long periods of calm and short moments of chaos. Veteran investors can attest to those moments of raw brutality, when price moves don’t neatly fit into models taught in business schools.

Typically, these brief periods of chaos and change are unpredictable in both timing and magnitude. Usually, many are caught unaware when they occur, and a great deal of wealth is lost. Take this year’s market action for instance.

The DeepSeek saga shocked the consensus narrative of technology investors, and more recently, U.S. President Trump’s Liberation Day tariff announcements on imports sparked an equity melt-down and massive volatility across asset classes.

Crashes and catastrophes in markets tend to be a lot more frequent than people realise. And when they occur, it’s usually uncertain when things will calm down. If it’s difficult to anticipate a regime change, it’s also just as difficult to know when the change will end.

I recalled the dark days of the Eurozone crisis; we were all unsure whether the European Union will survive intact, and frightened about what debt defaults from the southern European countries could mean. This was also true five years ago during the Covid pandemic, when countries shut their borders and the world suddenly came to a halt.

If these market shocks can’t be prepared for, and they occur many times over an investor’s lifetime, how should wealth be managed then?

Convergent & Divergent Strategies

Thinking from first principles, all kinds of investment strategies or approaches fall into two buckets.

The first bucket is known as convergent strategies. They converge on a certain knowable mean, or equilibrium state when they succeed.

They rely on a stable, knowable world, on structurally unchanging environments. Many are familiar with them as they are the kind of investment approaches showcased in traditional finance textbooks.

Think of arbitrage. A buyer or seller expects differing prices of a certain asset to trade at a similar price in all markets it trades at. The arbitrager is expecting convergence to a price deemed fair by the market. Or in value investing, where an investor buys an undervalued asset expecting that it will converge higher to its fair value. Currency carry trades also fall into this bucket.

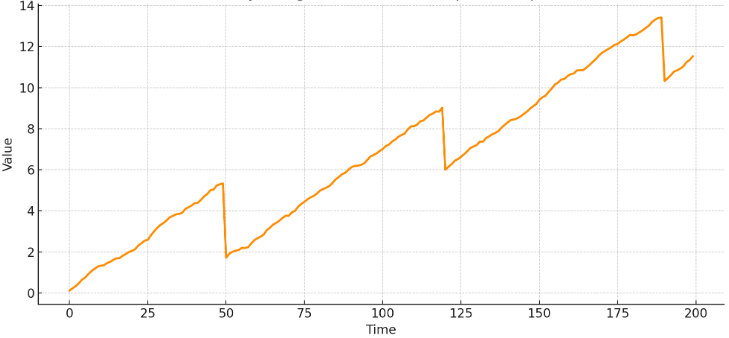

Their equity curves tend to look like the one below. Gains are gradually accrued most of the time, but losses may occur suddenly and quickly during regime changes, or when asset prices diverge away from their means. Successful convergent strategies will gradually recover as they adapt.

In the other bucket, we have the divergent strategies. Their nature is essentially the inverse of their convergent peers. Instead of converging onto a kind of equilibrium state, they diverge away from any known mean.

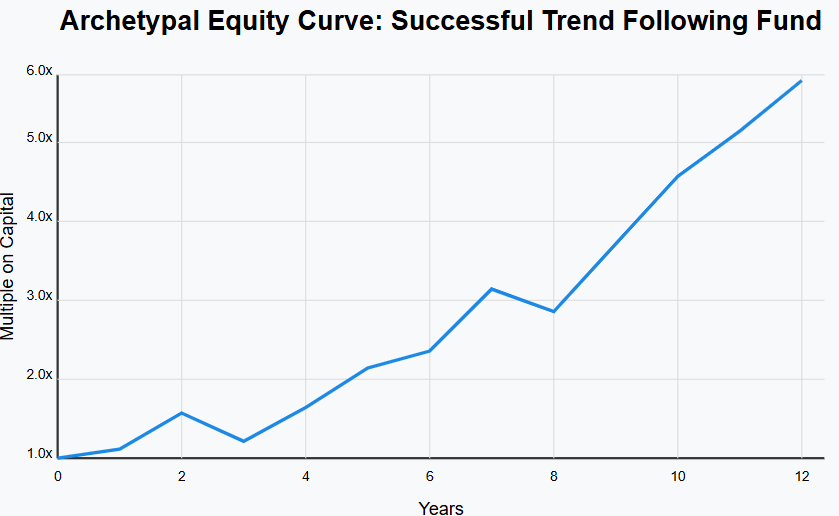

Think of Trend Following hedge funds. They essentially ‘buy high sell higher’. They bet that existing trends continue.

In the world of private markets, Venture Capitalists bet on start-ups that disrupt the existing incumbents and their way of operating. There is no ‘mean’ to bet on, but rather a new paradigm. Divergent strategies tend to have lower win rates but infrequent, lumpy profits when they make money.

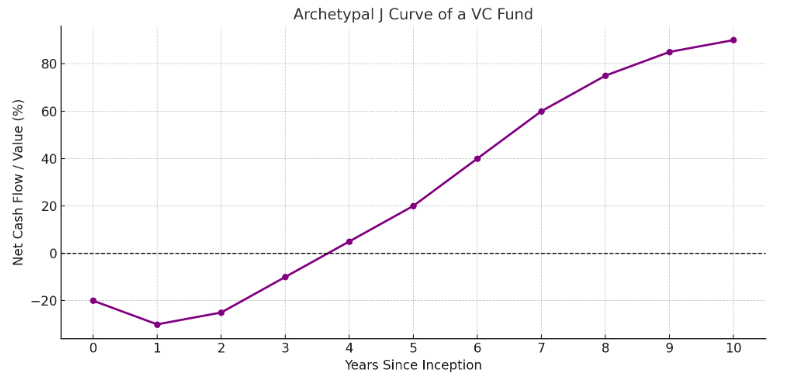

Their equity curves will usually show long periods of drawdowns before being in the black. The best way to visualise this is to reference the J-Curve from the Venture Capitalists’ world. Capital is drawn down and committed in the early years of a fund’s charter life, and investment gains are realised only much later if the overall operation is successful.

The performance of quantitative trend following strategies also look similar. Gains come in bursts during strong directional markets, followed by periods of sideways movements or choppy stretches.

Relying on one bucket means fully accepting and living through its characteristics.

The most successful investment firms have assembled portfolios of strategies from both buckets. In calm times, convergent strategies bring home the bacon, while during regime changes or market shocks, the divergent strategies benefit and contribute to the overall exposure. The allocation to each bucket can be 50-50, or any other combination that is acceptable and comfortable.

If effective, this arrangement helps to improve survivability over market cycles.

Allocating & Building Wealth For The Long Term As An Individual

To maximise opportunities, it’s vital to survive for the long haul in markets. However, longevity is a rarity in this business.

I’ve observed that during times of market shocks, investors tend to be forced out either because they were too highly geared or they reacted to fear. Somehow, market prices tend to test the maximum pain threshold of the crowd, as Barton Biggs pointed out (he said the market is a sadistic bastard). This should be avoided as much as possible, and it’s what advisers always meant when they say ‘capital preservation’.

So staying power should be prioritised, and that means using gearing prudently. The other way to build staying power is to ensure sufficient diversification to both convergent and divergent strategies as shared earlier.

The third point, which is underappreciated, is to have an income source that is independent of the market portfolio. This income source should ideally cover expenses. It can be a day-job income, or cashflow from a business, or side-gigs. Get as creative with this.

Doing so puts the investor into a situation of control, where sub-optimal decisions are less likely to be made. Anything that allows the investor to be as cool-headed as possible should be done. This hopefully, will help in better decision-making during chaotic moments.

As the portfolio is reviewed over time, the investor can consider topping up to the strategies that drew down the most, while gains can be realised on those that have done well. This ensures that the convergent-divergent mix remains as intended at the start.

It may be difficult to understand the catastrophe theory of Thom’s Swallow’s Tail, but with a healthy mix of convergent and divergent strategies, I believe the occasional unexpected market regime changes can be navigated, and wealth can be built for the long term.

Leave a comment