At every client event I go to, the question that never refuses to surface is whether the U.S. Dollar is going to collapse as countries de-dollarise. If it isn’t about the greenback, it’s concerns about the sustainability of America’s deficits.

It’s been more acute in recent times given the recently-held BRICs conference in Kazan, Russia, with more countries seemingly joining the intergovernmental organisation.

For years, Russian President Vladimir Putin has touted for an alternative to the existing global monetary system, which has been anchored by the U.S. Even Singapore’s former foreign minister George Yeo has expressed his concerns about the ‘weaponisation’ of the greenback by the U.S. government.

What’s really happening here? Is the primacy of the U.S. Dollar under threat? Let’s wind the clocks back seventy years to understand today’s situation to find our answer.

The Rise of the Dollar

When American, British and Allied troops were fighting Hitler’s armies back in the summer of 1944, American policy-makers would probably have been thinking about their role as a rising superpower.

It was a new world where the old European colonial powers were no longer influential, and one where they knew they had to compete with the Soviets and their vastly different economic and political system.

America’s leaders back then were scathed by the tragic experience of the Great Depression, and they were also tired of being ‘dragged’ into European conflicts, with the Second World War the second large fight in just a generation after the First World War.

There was a consensus among policymakers that the U.S. should and ought to be a different kind of superpower, even a ‘benevolent’ one, in contrast to ‘belligerent European powers’ like the British Empire. Naturally, they knew that through the titanic war effort, most Allied nations (including their British and Soviet allies) had borrowed heftily from them, and henceforth the U.S. currency will likely be the anchor in a post-WWII world.

The Bretton Woods system which was established in 1944 required countries to guarantee convertibility of their currencies into U.S. Dollars within a range of fixed parity rates, and the greenback being made convertible to gold bullion for foreign governments at a fixed price. This effectively established the primacy of the Dollar in international monetary arrangements.

After the war, America’s leaders were alarmed by the spread of communism. With much of the world in ruins and the Europeans focused on domestic reconstruction instead of imperial ambitions, the U.S. realised that they had to step up involvement globally to curb the spread of Soviet influence.

Policies were put in place to allow an expansion of trade between the non-Soviet aligned world, and loans were disbursed to countries deemed strategic to America’s interests, and to aid industrialisation. This was how a motley crew of controversial leaders such as Francisco Franco, Syngman Rhee, Chiang Kai-Shek and Ngo Dinh Diem were backed economically and politically by the U.S. In Europe, the famous Marshall Plan was rolled out – tying Europe to the U.S. militarily, economically and financially.

This is where we’ll need to understand global trade balances and capital flows. At the highest level, everything balances out. Keep this in mind as we go along.

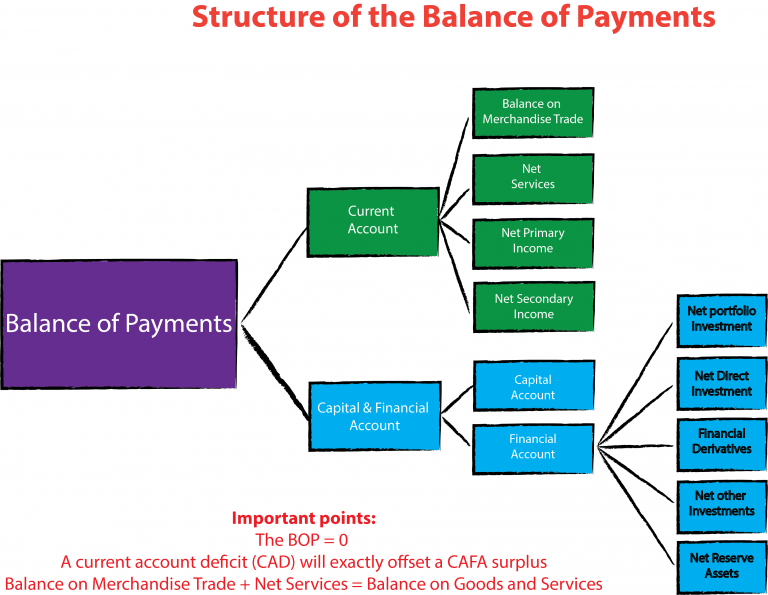

All countries have a Balance of Payments (BOP) – a way of accounting for trade and capital flows between the entities that transact with one another. I won’t go into too much detail, but I’ve asked Perplexity AI to summarise the components of the BOP concisely:

1. Current Account

This part tracks the flow of goods and services in and out of the country. It includes:

- Trade Balance: The difference between exports (goods sold to other countries) and imports (goods bought from other countries).

- Services: Transactions involving services, like tourism and banking.

- Income: Earnings from investments abroad and payments made to foreign investors.

2. Capital Account

This section records transactions related to financial assets. It includes:

- Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): When individuals or companies invest in businesses in another country.

- Portfolio Investment: Investments in stocks and bonds in foreign markets.

3. Financial Account

This part deals with changes in international ownership of assets. It includes:

- Investments: Buying and selling of financial assets, such as stocks and bonds.

- Loans: Money lent to or borrowed from other countries.

When an entity or individual sells a good to another entity/individual in another country, the transaction results in an exchange logged into the current account. Someone earns a currency, and another gets a good.

This also applies to investment transactions, in physical infrastructure such as a manufacturing plant built by a foreign company or a foreign pension fund investing in a domestic bond market.

The current account is meant to balance the capital and financial accounts within a country, although in reality this rarely occurs. Graphically, this is how the BOP’s structure looks:

Back to after the war: in the defeated countries of West Germany and Japan, American investment from the Marshall Plan led to rapid economic recoveries and a burgeoning market for U.S. exports, while import-orientated industrialisation, also more commonly known as import substitution, was pursued by Latin America and some parts of Asia.

Multiple rounds of tariff reductions were also pursued through the multilateral negotiations conducted under GATT over a period of almost two decades.

But in the 1970s and the 1980s, a confluence of events occurred that set the stage for today’s situation.

Firstly, Saudi Arabia, the lead exporter of crude oil, struck a deal with the Americans to hold their excess savings in U.S. sovereign debt (Treasuries). While the Saudis were still accepting non-dollar currencies such as Sterling for their oil exports, it was simply more convenient and cheaper to use the Dollar.

This led to the rise of the Petrodollar, where the Saudis and other oil exporters invested their Dollar receipts they received from selling to U.S. entities into U.S. financial assets such as Treasuries (recall the BOP and how everything has to balance out).

Secondly, there was a strong move towards free trade and deregulation in western developed countries, and the formation of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) encouraged a massive proliferation in trade.

As manufacturing in the U.S. became more expensive relative to other countries, American companies employed a great deal of ‘labour arbitrage’, taking advantage of cheaper labour markets and diversifying optimising their supply-chains and markets across regions and countries as much as American military might allowed them to.

Additionally, the collapse of the communist bloc and the Soviet Union, the opening up of China and the emergence of India exacerbated the trend of American outsourcing, particularly when many emerging markets pursued export-led industrialisation (exporting to the huge American market).

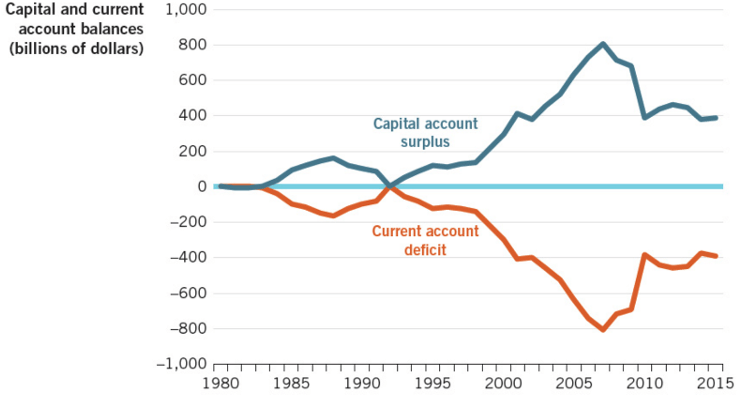

Together, this led to many countries exporting to the U.S. and the U.S. exporting the Dollar in return, resulting in a persistent decline in the U.S. current account balance as the large deficit in goods weighed on the data.

But recall the BOP explained earlier (everything balances out on the global level), everyone gets U.S. Dollars in return for trading with American entities, and these Dollar surpluses have to be ‘recycled’ somewhere. Because U.S. financial assets are the most liquid and largest in the world, they are the best place to ‘park’ surpluses.

This is how the greenback became the lubricant of global trade, and a key reserve asset of the world. This is also why traditional economic analyses and understandings of a country’s trade balances do not apply to the U.S. (dismiss those who tell you otherwise).

U.S. Default Woes

I’ll take a moment now to address concerns around the seemingly scary U.S. federal debt levels.

The balance sheet of a government isn’t the same as the balance sheet of a household.

Households don’t borrow in their own currency, and they have a timeline to repay. Governments can borrow in their own currency, and typically have no timeline to repay. In fact, throughout history, most governments including the U.S., have never actually ‘repaid’ their debt – they simply ‘grew’ out of it (countries which borrow in foreign currencies and lack the hard power of the U.S. belong in another category, but I won’t be explaining in this piece).

When economic growth rates are strong and consistently higher than the level of domestic interest rates, debt-to-GDP ratios will gradually decline.

This lack of understanding by observers has led to misunderstandings of government solvency, and it has showed up in U.S. default concerns going as far back as a century ago.

In 1944, an American economist Frank Dickson wrote a popular op-ed arguing that the only way the U.S. could survive economically was to default on its $200 billion of war-time debt. Dickson claimed that a whole generation would spend their entire careers working to pay off the national debt. President Harry Truman was also warned by the Council of Economic Advisors in 1946 about the enormity of the national debt that could crush the economy.

In hindsight, these concerns didn’t come to pass, as U.S. federal debt as a percentage of GDP was the lowest level in fifty years by the early 1980s. Strong multi-decade economic growth simply allowed the U.S. to ‘grow’ out of it.

This concept is harder to grasp when people are used to the concept of debt from a perspective of a household or corporation. What matters for countries isn’t the amount of debt they hold, it’s how burdensome that debt is to maintain over time.

A Different Kind of Decline

Michael Pettis aptly sized up the situation well on X (highlighted my emphasis):

It’s easy to see why many BRICS countries are wary of seeking an alternative to the dollar. The nine-nation group consists of 5 surplus economies and 4 deficit economies, with surpluses in 2023 collectively amounting to 3.5 times the deficits. That means that even if the BRICS nations were willing to accumulate assets in each other’s countries (and they are not), they would nonetheless have to balance their collective surpluses by acquiring a huge amount of assets outside the BRICs economies. (It would have been more than $780 billion in 2023).

Because this mostly means that they must acquire assets in the US and, to a lesser extent, in the UK and Canada, the BRICS are collectively very dependent on open US, UK and Canadian capital accounts. The BRICS trade surplus countries are, in order of size of the surplus, China (75% of collective 2023 surpluses), Russia, Brazil, UAE, and Iran. The trade deficit countries are India (76% of collective deficits), Egypt, South Africa and Ethiopia.

If the US were to reduce its trade deficit, perhaps by imposing controls on the ability of foreigners to balance their surpluses by acquiring US assets, this would be especially painful for the surplus members of BRICS, although much less so for the deficit members.

That is why BRICS members may occasionally fulminate against the dollar, but can’t do much about it as long as they must run large surpluses to avoid domestic disruption.

The real risk to the global dominance of the dollar is not that surplus countries seek an alternative. It is that the US itself will tire of running huge trade deficits that represent its absorption of the obverse of industrial and trade policies implemented abroad, and so take steps to reduce or even eliminate these deficits.

If the US were to do this, it would be almost impossible for surplus countries to continue running large, persistent surpluses, and they would be forced to reconcile domestic demand with domestic supply, most likely with a contraction of the latter.

While good for the global trading system and even, in the long run, for surplus countries, in the short run this would be extremely disruptive for the latter. That’s why what Washington does to the dollar is much more important than what Moscow and Beijing do.

De-dollarisation may be something that many desire, but far harder to do given what we understand of global trade and financial balances. Of course, alternative payment systems or regional currency blocs may arise, but this doesn’t necessarily entail an outright decline in the Dollar’s influence.

Until the industrial policies of the U.S. and surplus nations drastically change, I’m not really bothered by warnings of Dollar collapses.

Asset classes that have reserve-like properties may have their time in the sun as people seek for alternatives and diversifiers. However, as long as they are not as large and liquid as U.S. Dollars and the huge financial markets that the U.S. have (the most innovative companies, the most liquid bonds, etc.), it remains difficult to completely supplant the greenback’s reserve status.

Leave a comment